On 1 December, Taiwan’s foreign minister, Joseph Wu, gave a 15-minute television interview with journalist Stan Grant on the ABC. In the interview, Wu robustly described coercion from Beijing, including incursions from military aircraft, the constraint of Taiwan’s international relations, and the growing risk of conflict. He called for more support from Australia on the basis of shared democratic values and as a country also facing diplomatic and trade pressure from the People’s Republic of China.

The foreign minister also took time to explain how Australia’s ‘one China’ policy differs from Beijing’s ‘one China’ principle, noting that the deliberate ambiguity of Australia’s position on the status of Taiwan creates opportunities to build Australia–Taiwan relations and support for Taiwan in the international system even without formal diplomatic recognition.

The interview was only the most recent in a series of Australia–Taiwan events in 2020. In September, Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen participated in a high-profile webinar hosted by ASPI, the first time a Taiwanese president has specifically addressed Australia. There were also a number of activities that fell under the ‘track 2’ designation of unofficial exchanges.

Given the traditional focus of both Taiwanese and Australian foreign policy on China and the US, the visibility given to Australia–Taiwan relations is one of the notable developments of 2020.

On the Australian side, although relations have been on a steady positive trajectory for several years, Australia’s focus on China tended to marginalise Taiwan. The PRC applied direct pressure, as in the case of the proposed Australia–Taiwan free trade agreement in the early 2010s, but there was also an overall orientation of Australian policymaking towards China following the 2008 global financial crisis.

For its part, the Taiwanese government during the presidency of Ma Ying-jeou from 2008 to 2016 was also very focused on improving relations with the PRC. Highlights from that period include the negotiation of a cross-strait free-trade agreement in 2010 and a meeting between Ma and PRC President Xi Jinping in November 2015.

The geopolitical dynamic began to change in 2016, and by 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic, the deterioration of Australia–China relations, and Beijing’s increasing pressure on Taiwan had reshaped the parameters of Australia–Taiwan relations.

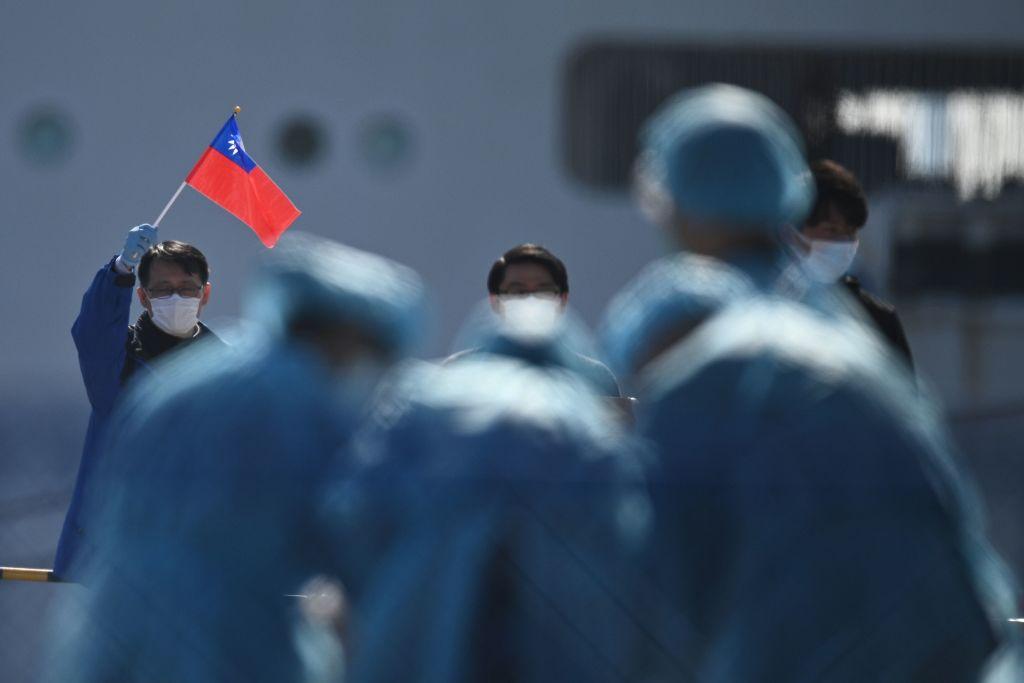

The pandemic has created a new vector for Taipei’s international relations. The Tsai government’s exemplary policy response to Covid-19, apart from being good for public health and economic growth in Taiwan itself, has been a win for Taiwan’s soft power and given it an obvious place in international discussions. Prime Minister Scott Morrison specifically identified Taiwan by name, without qualifiers, as a possible travel bubble candidate in November.

The tension between Australia and China has also worked to create a policy space for relations with Taiwan in the context of market diversification and international cooperation in the face of Beijing’s belligerence.

For Taiwan, the increasing intensity of the PRC’s military activity and the degree of uncertainty in US–Taiwan relations with President-elect Joe Biden’s incoming administration have given urgency to efforts by the Taiwanese government to explore all possible mechanisms through which it can maintain Taiwan’s security.

Strengthening bilateral Australia–Taiwan ties has made sense, then, in terms of the respective interests of both sides, but it is also capturing a genuine emerging interest and commitment to the relationship in government and policymaking, as well and in the media and public institutions, in a rapidly changing region.

Nevertheless, the absence of formal mutual diplomatic recognition remains a structural constraint on the relationship. It limits the contact between government ministers and presents barriers to critical relationship vectors in defence and intelligence. An interview between the Australian national broadcaster and the Taiwanese foreign minister takes on special political implications for Australian foreign policy.

A risk to Australia–Taiwan relations is that goodwill, mutual concerns and new needs that have arisen during the pandemic will come up against these unique structural restraints, generating misunderstandings and mismatched expectations. In his careful responses to Grant’s questions about Taiwanese expectations for Australian involvement in the defence of Taiwan in the event of a military crisis, Wu showed that Tsai’s government is attuned to this issue.

Both sides, but especially Australia, lack policy depth towards the other—it is only a fraction of the capacity Australia and Taiwan maintain for relations with the US and China. The next year will signal whether the new possibilities for Australia–Taiwan relations dissipate with the passing of the pandemic or are sustained on secure foundations.