It’s been an interesting 48 hours in space news. For starters, the Trump administration’s decision to fast-track US strategy for a return to the moon, aiming for American astronauts to land at the lunar south pole by 2024 (instead of the earlier plan of 2028) caught everyone by surprise—including NASA. The announcement generated intense debate about whether the new timeline is practicable, what it means for NASA’s behind-schedule and over-budget Space Launch System rocket, and whether Congress will fully fund such a move. It’s clearly designed to achieve a lunar landing in time for the end of what would be Donald Trump’s supposed second term in office and, as explained by Vice President Mike Pence, it’s set in the context of a new space race against China.

For space watchers, that was exciting enough.

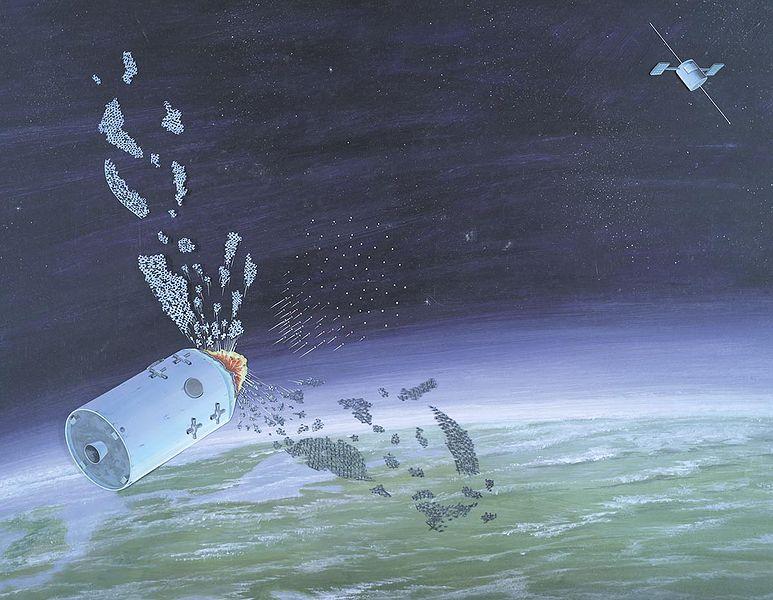

But the more dramatic news, which broke late Wednesday evening, was India’s test of an anti-satellite weapon (ASAT) in low-earth orbit (LEO). Promoted as a great achievement for India, ‘Mission Shakti’ involved the destruction of a 740-kilogram microsatellite by a missile carrying an ASAT. The mission was led by the Indian Defence Research and Development Organisation, the government agency responsible for India’s military space capability. The satellite, known as ‘Microsat R’, was a ‘live’ satellite (meaning it was in active use as a military reconnaissance satellite), though clearly it could also be considered a prospective target for an ASAT test.

The low altitude—300 kilometres—of Microsat R means that most of the debris will re-enter the atmosphere and burn up quickly. That distinguishes the Indian test from China’s 2007 ASAT test against the Fengyun-1C satellite at 800 kilometres, which produced a large debris field and generated significant international opprobrium for Beijing.

The Indian test is much closer in nature to the US 2008 Burnt Frost exercise, in which a US Navy cruiser launched an SM-3 missile defence interceptor against a malfunctioning US satellite in a decaying orbit at 280 kilometres. The ostensible aim was to prevent toxic chemicals from spreading in the event of an uncontrolled re-entry—but the mission also demonstrated an ASAT capability to Beijing following its test in January 2007. Although much of the debris re-entered and burned up quickly, some was thrown higher into LEO and was a hazard for close to 18 months.

The Indian ASAT test appears to be an attempt to demonstrate parity between Delhi and Beijing on counterspace capability—at least against very low altitude LEO satellites. As Brian Weeden and Victoria Sampson note in their 2018 global counterspace assessment, China has certainly deployed direct-ascent ASATs designed to destroy US satellites in LEO.

Those weapons could easily be directed against Indian satellites too. In a crisis, that would give China the ability to reduce the terrestrial capability of Indian military forces. It would compromise effective command and control and eliminate space-based intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance, leaving Indian forces deaf, dumb and blind. Without an Indian ASAT capability, China has little to fear from an Indian response in kind and could gamble that Delhi wouldn’t risk escalation—for example, by using nuclear weapons.

So, it’s likely that India’s actions were motivated by a desire to establish credible space deterrence against China, and potentially against Pakistan (though it must be noted that the Pakistani space program is nowhere nearly as advanced as India’s). The test also contributed to India’s ability to undertake ballistic missile defence. An ASAT test against a LEO-based satellite demonstrates the ability to intercept longer-range missiles, which fly faster and higher than short-range tactical missiles that generally fly within earth’s atmosphere. That’s a message to both Pakistan, which has Shaheen-II and Shaheen-III medium-range ballistic missiles, and of course China, which has a full range of ballistic missile capabilities that can reach targets across the length and breadth of India.

The window of opportunity for conducting ASAT tests may be closing soon. There are long-running efforts to promote and strengthen space arms control and legal norms against space weapons. Nothing in the panoply of current space law prevents testing of ASATs, but China and Russia are promoting the draft UN treaty banning the placement of weapons in space (the ‘PPWT’ proposal) and continue to push the proposed Prohibition on an Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS) agreements. The US and other nations are rejecting these ideas because they’re unverifiable and would leave Chinese and Russian direct-ascent ASATs intact. India may have decided to ensure it has a declared ASAT capability now to avoid any possible political fallout from refusing to sign or withdrawing from such agreements in the future.

From India’s perspective, the ASAT test is also an important achievement that boosts national prestige. Prime Minister Narendra Modi promoted the ASAT test as a sign of India’s entry into a select club: ‘The launch under Mission Shakti has put our country in the space super league.’

With a national election coming up, and Modi promoting his defence and national security credentials, especially after the Indian response to Pakistan following the Pulwama attack, the ASAT test plays to his domestic political agenda, as much as it seeks to emphasise India’s prestige globally.

Of course, blowing up satellites doesn’t have the same ‘feel-good’ effect as other types of space activities, such as putting astronauts back on the moon. The fact that India’s test was carefully designed to avoid a large debris field is commendable. Yet it has already generated considerable criticism because every test is perceived to weaken promoted norms against space weaponisation, making it easier to proceed down a slippery slope towards an arms race in space.

Will China take India’s ASAT test as a justification for accelerating and broadening its ASAT program? How might India then respond? How might the US respond to an accelerated Chinese ASAT program? The potential for an action–reaction space arms race coming out of Asia shouldn’t be ignored.

China’s ASAT program since 2007 has emphasised co-orbital testing, which is better suited to ‘soft kill’ mechanisms, including techniques that disable rather than physically destroy a target. It’s not in any state’s interest to fill space with debris that hinders access, or worse, risks a ‘Kessler syndrome’ event of cascading collisions generating expanding clouds of space debris. India can certainly make a military case for ASATs to ensure parity and strengthen space deterrence against Chinese counterspace capability, but it would be wise to leave ‘hard kill’ behind and develop more sophisticated ‘soft kill’ techniques that avoid the worst outcomes of space war.