This article is the first in a series on ‘Women, Peace and Security’ that The Strategist will publish over coming weeks in recognition of International Women’s Day 2017.

Australia’s first National Action Plan (NAP) on Women, Peace and Security (WPS) was launched five years ago this week on International Women’s Day in 2012. The NAP sets out how Australia will implement UN Security Council Resolution 1325 and the broader WPS agenda, which is an approach that has also been taken by more than 60 countries around the globe. With Australia’s first NAP set to expire in 2018, discussion and debate is already underway about how the whole-of-government plan can be improved to ensure that Australia is delivering on its commitments to WPS.

Among the issues to be considered as part of the wide-ranging review will be how to address the weaknesses in the existing NAP. An independent interim review in 2015 found that monitoring and evaluation measures weren’t sufficient to measure progress and impact. That review also found that funding and resource allocations across government agencies were uneven. The next NAP needs to be strengthened in some of those areas and could draw on the examples of other countries.

The focus of Australia’s NAP is largely external, given that Australia isn’t currently experiencing armed conflict. Nonetheless, it has domestic implications in terms of the development of policy, funding and the structure of security institutions that deploy offshore (e.g. the ADF). In the five years since the adoption of the NAP, the nature of conflict and potential drivers of instability have continued to evolve and change. Discussion is already underway about the extent to which security challenges such as countering violent extremism, issues of justice and accountability, or approaches to humanitarian and disaster response may necessitate inclusion in the next NAP.

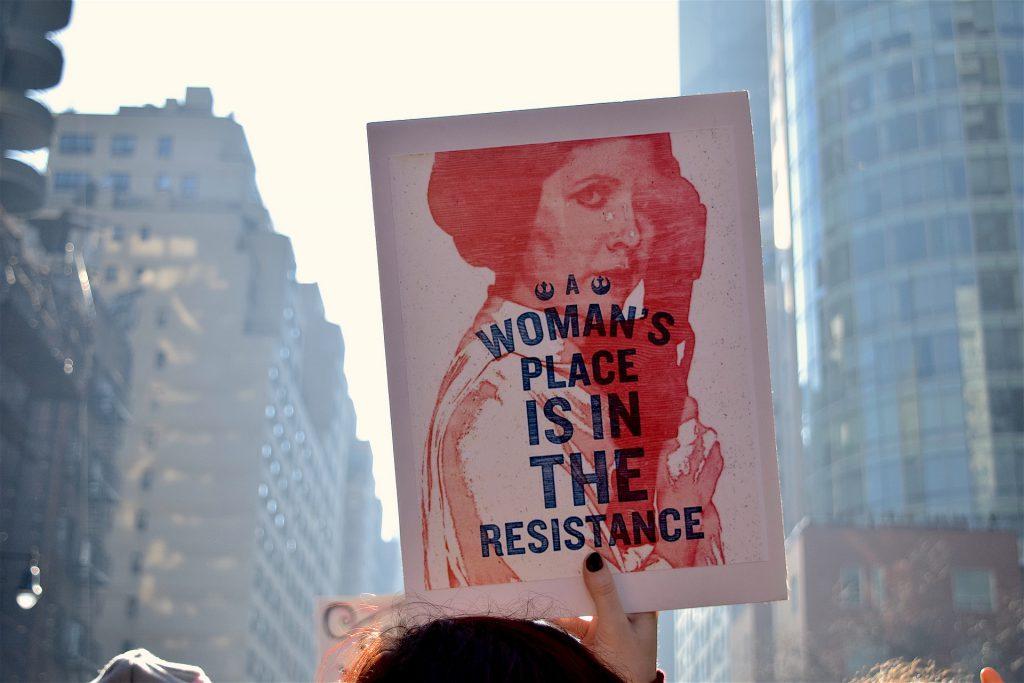

At the same time as looking forward, however, recent global developments suggest that efforts to progress WPS will need to remain on the defensive over coming years. During an address to the UN Human Rights Council last week, Secretary-General Antonio Guterres expressed concern that: ‘Hard fought gains on women’s rights are being chipped away.’ Indeed, momentum on the issue has slowed down in the UN Security Council and is likely to face further challenges.

Reforms to increase the representation of women in the ADF haven’t been immune from criticism either. The cultural reform program in the ADF—intended, in part, to increase diversity—has been labelled ‘PC rubbish’ that would detract from Defence’s core goal of ‘war-fighting’. As my ASPI colleagues Andrew Davies and Mark Thomson have previously countered, that view may be fine if you want to keep ‘the ADF as a demographic heritage theme park’. But the ADF needs to be responsive to the evolving nature of conflict. Modern conflict situations (such as Afghanistan, or peacekeeping operations) often require engagement with the local civilian population. In these contexts, female military personnel may be in a better position to engage with the local women about potential threats. Ignoring the need to increase the number of women in the ADF—or failure to do so—risks diminishing the ADF’s future capability and operational effectiveness.

The same applies to the related but different issue of integrating gender perspectives. It’s something the international community still struggles to get right—a recent report addressing the WPS implementation gap found that the Security Council has a ‘tendency to overlook gender’ in ‘emerging or drastically deteriorating’ situations. The ADF’s experience in operations in Afghanistan, providing humanitarian and disaster relief in Fiji, as well as lessons from military exercises such as Talisman Sabre, have demonstrated the importance of integrating gender perspectives as part of military operations. Considering gender—that is, the needs of women and men—as part of policy, planning, operations and intelligence will be essential if this aspect of the WPS agenda is to be fully realised.

While the NAP is an important and internationally recognised mechanism to measure Australia’s commitment to WPS, it’s not the only measure of the government’s commitment. As the UN’s 2015 Global Study on WPS noted, NAPs are ‘simply processes and facilitators of actions, not ends in themselves.’ Ultimately, the commitment is measured by what change is affected on the ground through policies and reforms. That requires more strategic direction. As I’ve argued previously, the 2016 Defence White Paper fell short in that area. We need to be asking more deliberate questions about what implementing WPS means for our approach to international defence engagement and foreign policy.

As we mark International Women’s Day this Wednesday, we need to consider how we consolidate and build on existing initiatives to progress WPS, as part of and beyond the next NAP. We’ll be continuing that debate here at The Strategist with a series of posts exploring efforts to progress WPS in the international community, as well as what that means for Australia’s defence, national security and role in the world. It’s an important discussion that we need to have.