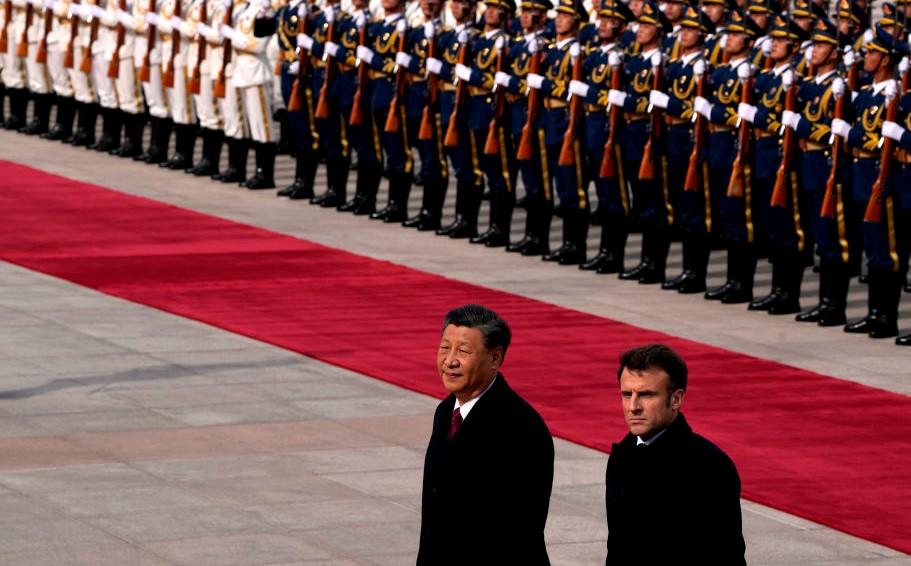

Pressing Chinese President Xi Jinping to ‘bring Russia to its senses’ in the forlorn hope of ending the war in Ukraine is all the rage among European statesmen. Over the past two months, French President Emmanuel Macron, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock and Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez have all visited China. The three urged Xi and his inner circle to call Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, bring everyone to the negotiating table and persuade Putin to end the war. Or, at least, establish a ‘lasting peace.’

In post-summit statements, Xi paid lip service to ‘peace talks’ and the reprehensibility of nuclear war, but European desires that he coax Putin into ending the war will keep falling on deaf ears.

So far, too many Western leaders have disregarded the gap between what China says and what it does. Their calls for Beijing’s intervention show that they see the Chinese Communist Party’s external beliefs and behaviours through their own liberal lens, but that is not how China conducts world affairs.

For decades, liberal leaders got China terribly wrong. Officials and academics prophesied that Western capital, economic engagement and political accommodation would liberalise China. Many clung to this misguided hope despite mounting evidence to the contrary in the early 2000s.

China’s domestic human rights violations and use of political oppression, coupled with nefarious inter-state practices like forced technology transfers, intellectual property theft, ‘brute force’ economics and disputed sovereignty seizures have proven that rapid economic development need not come alongside stronger political freedoms or democracy.

Although Europe has begrudgingly tolerated China’s competitive authoritarianism, it is now in danger of succumbing to another beguiling delusion: that Beijing can be an ‘honest broker’, an objective force for good in the world that conforms to a liberal, rules-based order.

But Beijing is not a kindred liberal spirit and efforts to coerce Xi into intervening on behalf of peace expose the naivety of Europe’s China policy.

Such efforts assume that Chinese proclamations about a ‘democratic’ world and ‘win–win cooperation’ aren’t sly slogans but actual operating principles. This relapse of foolish faith in China’s altruism ignores the logic behind Beijing’s continued decision to vocally support Vladimir Putin’s Russia despite its invasion of Ukraine.

For Xi, it pays to stand behind Putin for four reasons.

First, Russia remains a great power and founding partner of China’s anti-US coalition. Prussian statesman Otto von Bismarck allegedly remarked that in a world order of five states, one should always be in the group of three.

The same concept applies to today’s world order of three major powers—the US, Russia and China. It’s best to be the duo. Beijing and Moscow are cooperating with each other to resist an alleged ‘all-round containment, encirclement and suppression’ by the US. Sino-Russian relations are invigorated not by ties of history, language or culture, but by shared antipathy for the US and a desire to diminish its global influence.

As Xi told Putin before leaving the Kremlin in March: ‘Right now there are changes—the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years—and we are the ones driving these changes together.’ The Ukraine war may have hindered Russia’s global power, but Xi still has a willing and able ally in Putin. The more Xi helps Putin withstand sanctions and international criticism, the weaker Washington appears.

Second, Xi wants predictable relations with China’s neighbours and great powers so it can focus on competing with the US. Historically, Sino-Russian relations have rarely been chummy. The two major land powers together make up much of Asia and share the third largest international land border.

A reliable pariah-neighbour is better for China than an unknown quantity or political vacuum. This is why Xi and Putin have met more than 40 times in the past decade and call each other ‘dear friend’. Invasion or not, Xi will continue to support Putin to prevent political instability that could upend Eurasia.

Third, the Ukraine war itself benefits China. Because of the war, China has been able to buy Russian oil, gas and coal at cheaper prices, after European customers began shopping elsewhere. The war has also provided China with a treasure trove of lessons on how to invade—or not invade—another state. Those insights, ranging from urban warfare to information operations, could shape Beijing’s own plans for a forceful reunification with Taiwan.

And perhaps most importantly, Xi likely believes the longer the war in Ukraine goes on, the more it shifts Washington’s focus away from East Asia, exhausting its munitions depots and political will to resist another conquest.

Fourth, supporting Putin costs Xi little. During the March summit, Xi bypassed Putin’s wish list of lethal aid and a second Power of Siberia pipeline. Instead, he only gifted Putin enough moral support to prove that Russia wasn’t completely isolated and enough non-lethal aid to sustain the flagging Russian war effort. Putin has little choice but to accept these symbolic gestures.

European leaders’ delusions about China’s ability, or desire, to end the invasion are dangerous, given the concessions they offer to enlist Xi’s help. During his visit, Macron invited a massive business delegation and distanced France from the US in the pursuit of ‘strategic autonomy’—a favourite concept of Xi’s. In return, he received nothing. The rest of Europe should take notice. Xi has no compelling reason to meddle in a conflict that benefits China, especially when it means lecturing a friend with a common enemy.

Xi’s late April phone call with Zelensky was hailed as a positive development, but little has changed since, nor will it. Xi will continue playing the enlightened peacemaker while privately bolstering his dear friend’s regime. For now, there’s little he wants to change, even if he could.