As readers of this post will undoubtedly recall from schooldays spent declining Greek nouns, the word strategos means ‘general’; hence our word, ‘strategy’, or the ‘art of generalship’.

As readers of this post will undoubtedly recall from schooldays spent declining Greek nouns, the word strategos means ‘general’; hence our word, ‘strategy’, or the ‘art of generalship’.

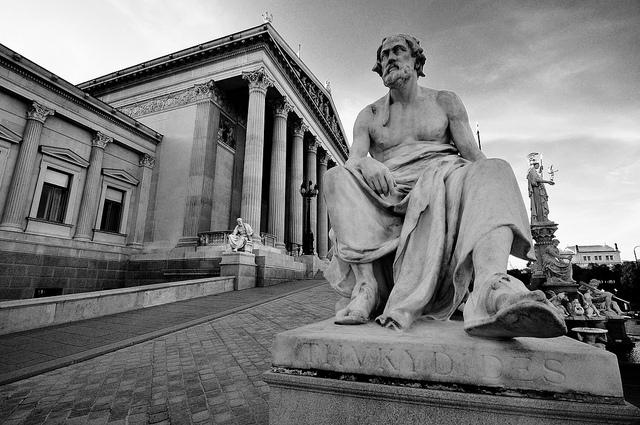

Of course leadership in war was never really simple, even back then before crypto codes and chinagraph pencils were invented. Source documents from the ancient period normally focus on the victory itself, or who won, rather than the specifics of the clash of arms and details of battle. When an incident is highlighted, it’s often because something out-of-the-ordinary has occurred. Roman writers take the tactical method of the legionaries for granted, just as Thucydides felt little need to describe the terror and chaos of charging in the front rank of a phalanx. Perhaps he thought all his readers would have ‘done’ that, just as he had.

Yet it’s obvious that even these early chroniclers understood victory depended on much more than just using successful tactics to gain the advantage. Gradually, the word ‘strategy’ began to include all those ancillary things that go towards explaining why one side wins and the other is defeated. The sort of things we think of when we talk of strategy today.

The Byzantines were among the first who forced the word to do more than it was meant to. Ever industrious, they began making it work overtime, turning the strategos into rather more of a military governor than simply a senior officer. But it was a world attempting to make sense of the massive wars that convulsed Europe in the nineteenth century that really started the trend that burdened the word with more meaning than was ever intended.

Rather like the rest of us, the poor word has been forced to carry more and more responsibility with less and less pay. Today, with merely the addition of an occasional prefix (such as ‘grand’), it’s become increasingly loaded. ‘Strategy’ now covers everything from the work of a commanding general right through to culture (PDF) (making us all think correctly) and business (so we’ll buy more widgets). It’s now being expected to define the thinking work of politicians, too. We look expectantly to our leaders, waiting for them to offer us a plan (a ‘national strategy’) that will somehow make the country rich and us prosperous. Ask yourself; is this really fair?

In the last couple of months two leading strategists have decided the answer to this question is a resounding ‘no’. Lawrence Freedman (my former professor of War Studies at Kings College, London) weighed in with a 752-page tome that ranges knowledgably over every aspect of the subject; and Hugh Strachan (who hosts delightful lunches at All Souls, Oxford) provides a sharp, refined, analysis of the subject, always keeping it firmly lodged in historical perspective. Their contributions to the debate are different and worth reading, because strategy is about victory. It is, in other words, the ultimate reason for war.

And this is why our idea about what strategy might be has expanded over recent years. But I’m already approaching the end of my word limit for this post and I haven’t even begun to proffer my own definition—so perhaps it’s better to attempt to identify what it’s not.

If you wasted your childhood like me, playing games called ‘Diplomacy’, you were secure in the knowledge that, as supreme leader, you never had to answer to the populace. That was the real-world case for dictators like Hitler and Stalin, too. They could ally with one another to divide up Poland before suddenly attempting to tear one another apart. For them, grand strategy really did involve complete mastery of the nation’s resources.

But leaders today, and particularly ones in democratic countries like our own, don’t have that luxury. Take our relationship to the East China Sea. Personally, I think Australia should make it clear we’ll be keeping well away from any dispute in those waters—I think the danger of getting sucked into a disastrous, accidental conflict is far too great. But that’s my political perspective, if one informed by strategic understanding. Others, and perhaps most Australians, would disagree. Many couldn’t imagine us standing by (as the Canadians and Brits did during Vietnam) if the US was at war.

This is why the decision to go to war will never be made on strategic grounds alone: it’ll be taken on political, cultural and emotional ones. That’s why I believe we’ve got to be careful when we attempt to use strategy as an analytical tool. It can inform our decisions, but it’s important to remember strategy remains, simply, a method that’s used to achieve a result. Primacy should always be given to politics. Unfortunately.

Nic Stuart is a columnist with the Canberra Times. Image courtesy of Flickr user Chris JL.